An article in the New York Times relates new findings on aquarium fish behavior. Turns out they are much more aggressive than their counterparts in the wild:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/27/science/fish-in-small-tanks-are-shown-to-be-much-more-aggressive.html?ref=science

It makes lots of sense when you think about how fish in the wild have a whole pond, lake, river or ocean to swim around in. Should they encounter an aggressive conspecific or hostile other species, there's plenty of room to swim away. Not so in the confined space of a small aquarium.

One thing the article does not address is differences between species in their responses to aquarium overcrowding. Solitary species must surely get more aggressive than social fish who thrive in schools.

My brothers and I kept freshwater aquarium fish for many years, and we did lots of research on what kinds of fish to get, making sure we get species that like the same water and temperature conditions, and were social and non-aggressive. Many of the fish we used to keep were smalls ones that were happiest in schools, like South American tetra species, or Asian species like the zebrafish and the cherry barb. The optimum size of the school for a given fish tank volume must differ between species.

The fish used in the study, the Midas cichlid, is by nature territorial and aggressive, so the effects of living with other fish in a small fish tank on aggression must be more acute in this species that in others. Still, the study is important in helping us be aware of the silent stress that fish may endure in aquarium tanks. Maybe it will point us to what species are suitable to aquarium life and which are not, what the optimum tank sizes for different fish species are, and in what numbers of fish to keep them in a given volume of tank.

Thursday, December 29, 2011

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

End of the Month Science Music Video: They Might Be Giants (Photosynthesis)

They Might Be Giants - Photosynthesis

Friday, November 18, 2011

Can the internet help save one of the most biodiverse spots on Earth?

Last summer I had the great privilege of visiting what scientists have identified as possibly the most biodiverse spot on Earth (one hectate of this place contains more tree species than are native to all of North America). It is also home to some of the numerous indigenous cultures that still lead a traditional existence. The forest is Yasuní, in Ecuador, where I was born. None of my relatives in Ecuador have been there, so it was a special privilege to tell them about this national treasure while lies in the tropical east of the country.

Because it sits on large oil reserves, the forest could easily succumb to the pressures of an oil-addicted world, plus the needs of a developing nation. In addition to the toxic pollution of oil extraction wold come the colonization, deforestation, illegal logging, and unsustainable hunting that comes with the oil-access roads.

But the forward thinking government of Ecuador made a bold proposal to save the park from this threat. In 2007, the government of President Rafael Correa proposed to keep the oil under Yasuní permanently under ground in order to protect the park, fight global warming and preserve the lands of the indigenous populations there. In exchange, the government would receive several billion dollars from developed countries.

So far, donations from governments have not been forthcoming. At a screening for Yasuní, Two seconds of life, a documentary about the forest by a team from Ecuador, Austria and the US, which premiered in the US in the Ecuadorian Embassy in Washington, DC, I heard talk that instead of governments, perhaps the private sector might be a better source of donations.

Perhaps. But I also wondered if maybe small private donations might also help. So recently I went to the Yasuní-ITT Trust Fund, a fund administered by the United Nations that will take donations and help pay for this innovative preservation initiative. I saw that one could make personal donations, and so I made one. I was happy to see that I was not alone.

As you can see above, there were personal donations from individuals in developed countries, especially the US and the UK. But there were even donations from people in poor countries, including Ecuador. Maybe with some better marketing and some savvy use of the internet, the world could be crowd-sourced for funds to help save this jewel among forests!

But another source of hope lies not outside of the park, but within, with the people who live there. When I visited the forest, I stayed at the Napo Wildlife Center, an eco-lodge run by an the indigenous Kichwa community of Añangu, within the park boundaries. I spoke to one of the older guides from the tribe, who told me that before they started the eco-lodge, his people, who are a river people who depend completely on the forest for food and medicine, faced the threat of outsiders deforesting and hunting, with the government doing nothing to prevent it. They took matters in their own hands, developing with the help of outside NGOs a wildlife center and eco-lodge, which now serves as a home-grown and sustainable alternative to oil-development. Other parts of Ecuador may benefit from this model, including the unique and endangered cloud forests on the Western slopes of the Ecuadorean Andes, which were recently featured in the New York Times.

I didn't take many photos during my trip; I relied on my travel companions to do that. But here are a few of the photos I did manage to take. Nothing like experiencing it with your own senses though.

If you'd like to see some better photos, check out photos on Flickr tagged "Yasuni".

You can also check out a photo slideshow of Yasuní from Science magazine.

And please consider donating to the Yasuní-ITT Trust Fund! Show Ecuador and the world that there is an alternative to destructive and irreversible oil development, and that we care.

|

| On the lake, by the Napo Wildlife Center, Yasuní National Forest, Ecuador. |

But the forward thinking government of Ecuador made a bold proposal to save the park from this threat. In 2007, the government of President Rafael Correa proposed to keep the oil under Yasuní permanently under ground in order to protect the park, fight global warming and preserve the lands of the indigenous populations there. In exchange, the government would receive several billion dollars from developed countries.

Trailer for Yasuní - Two Seconds of Life, a wonderful documentary about Yasuní Forest, the forces that threaten it, and the plan to save it.

So far, donations from governments have not been forthcoming. At a screening for Yasuní, Two seconds of life, a documentary about the forest by a team from Ecuador, Austria and the US, which premiered in the US in the Ecuadorian Embassy in Washington, DC, I heard talk that instead of governments, perhaps the private sector might be a better source of donations.

Perhaps. But I also wondered if maybe small private donations might also help. So recently I went to the Yasuní-ITT Trust Fund, a fund administered by the United Nations that will take donations and help pay for this innovative preservation initiative. I saw that one could make personal donations, and so I made one. I was happy to see that I was not alone.

|

| Click on graph for larger view. |

As you can see above, there were personal donations from individuals in developed countries, especially the US and the UK. But there were even donations from people in poor countries, including Ecuador. Maybe with some better marketing and some savvy use of the internet, the world could be crowd-sourced for funds to help save this jewel among forests!

But another source of hope lies not outside of the park, but within, with the people who live there. When I visited the forest, I stayed at the Napo Wildlife Center, an eco-lodge run by an the indigenous Kichwa community of Añangu, within the park boundaries. I spoke to one of the older guides from the tribe, who told me that before they started the eco-lodge, his people, who are a river people who depend completely on the forest for food and medicine, faced the threat of outsiders deforesting and hunting, with the government doing nothing to prevent it. They took matters in their own hands, developing with the help of outside NGOs a wildlife center and eco-lodge, which now serves as a home-grown and sustainable alternative to oil-development. Other parts of Ecuador may benefit from this model, including the unique and endangered cloud forests on the Western slopes of the Ecuadorean Andes, which were recently featured in the New York Times.

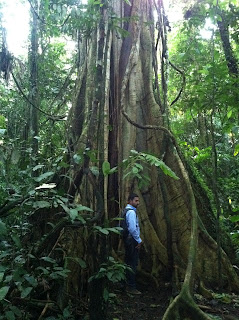

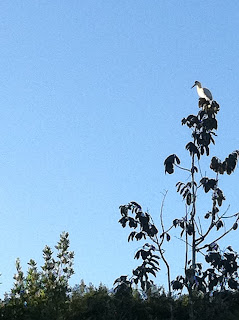

I didn't take many photos during my trip; I relied on my travel companions to do that. But here are a few of the photos I did manage to take. Nothing like experiencing it with your own senses though.

|

| My friend by the base of a tall ceiba tree. |

|

| Myself at the canopy of a ceiba. |

|

| Capped Heron (Piherodius pileatus) |

|

| A species of Amblypigid, or tailless whip scorpion, an arachnid related to spiders and true scorpion. This one was the size of my hand. |

|

| Guides from the Napo Wildlife Center. The gentleman on the right is a native of the Kichwa Añangu community. |

You can also check out a photo slideshow of Yasuní from Science magazine.

And please consider donating to the Yasuní-ITT Trust Fund! Show Ecuador and the world that there is an alternative to destructive and irreversible oil development, and that we care.

Monday, October 31, 2011

End of the Month Science Music Video: Guided By Voices (I am a scientist)

Guided By Voices - I am a scientist

Friday, October 7, 2011

Chemistry Cat

Chemistry Cat is a great source for the dorkiest chemistry jokes and puns wisdom.

This is my favorite so far:

Monday, September 26, 2011

End of the Month Science Music Video: Dandy Warhols (I am a scientist)

The Dandy Warhols - I am a scientist

Saturday, September 10, 2011

Guest blog post in Scientific American

When a group of high school students from New Hampshire contacted the National Science Foundation for advice on their science project, they described what sounded like a far-fetched idea: to make an organism photosynthetic. But it turns out this experiment has been conducted numerous times in nature, and very recently, in the lab. Green corals, green sea slugs, and even green fish. This article summarizes the incredible partnerships between photosynthetic organisms and non-photosynthetic hosts, and what we can learn from these green partners about how to better utilize the energy from the sun. Read more in my guest blog post in Scientific American, "It's not easy being green, but many would like to be".

Thursday, September 1, 2011

End of the Month Science Music Video

The August edition of End of the Month Science Music Video comes in a day into September due to some travel disruptions I experienced thanks to Hurricane Irene. The video came to me courtesy of a great friend of mine, and is a clever and educational promo for the Marie Curie Actions, a funding mechanism for researchers in Europe.

Danke sehr S. N. for that clip!

Danke sehr S. N. for that clip!

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Beyond the edge of the sea: art and science from the ocean's deep

The National Science Foundation is the main source of basic research funding for science and engineering in the United States. But on the third floor of the NSF one can find a fascinating interface between science and art. Until the end of this month, the Art of Science, a committee of volunteers interested in the meeting of the worlds of science and art, hosts a traveling exhibit called Beyond the Edge of the Sea, a collection of watercolor illustrations of the fantastical marine life found around deep-sea hydrothermal vents during expeditions in the deep-ocean submersible, Alvin. The exhibit is the product of a partnership between illustrator Karen Jacobsen and oceanographer Dr. Cindy Lee Van Dover. Both were at the NSF this week to talk about their work in Alvin and the process of observing and collecting samples at great depths, a few thousand meters below sea level, and the process of capturing the images by watercolor.

|

| The scientist (back to us). |

|

| The artist. |

Some of my favorite drawings are one with notes from the artist, most of which are technical notes, but there is a tone of excitement, curiosity and fascination which combined with the beautiful illustrations make this exhibit so compelling.

Next stop for the exhibit: Madison, Wisconsin. Be on the look out for this magic visit from the ocean's deeps. You can get a preview of the images here. For more detailed information on the biology and geology and chemistry of the vents, refer to this easy-to-read guide (PDF).

UPDATE: A recent story on NPR on "The Deep-sea Find That Changed Biology".

Sunday, July 31, 2011

End of the Month Science Music Video: The Flaming Lips (Race for the prize)

This month's End of the Month Science Music video is Race for the Prize, by The Flaming Lips, about two scientists racing, for the good of all mankind.

Monday, July 11, 2011

A modest proposal for DC's official crustacean

|

| Rock Creek, Washington DC. Photo by M Vinces. |

The other day I was in the National Zoo in Washington DC and I walked into the Small Mammal House since it was an especially sleepy day at the zoo and most of the critters were resting and hiding away and I was in the mood for furry cuteness. The Small Mammal House seemed like a good bet. I wasn't disappointed. I saw quite a few sengis, aka "elephant shrews" (a misnomer, since they are not true shrews, but interestingly are actually more closely related to elephants and manatees than to true shrews). They were weird and adorable which is just what I wanted.

On one of the notes outside the glass enclosure containing some rare golden lion tamarins was a box describing the importance of habitat protection for saving threatened species, in which they used as an example, the importance of closing certain trails in the nearby Rock Creek Park, because these areas are the sole habitat of an endangered "shrimp-like species". Intrigued by the notion that this urban park was the unique habitat of a rare species that existed no where else on the planet, I looked around the Small Mammal House for more information about this mysterious "shrimp-like creature". I didn't find any, so I got on the Google and found out the little rascal is called Hay's Spring Amphipod and it lives no where else but for a few springs in in the zoo and in the adjacent Rock Creek Park. Surely the Invertebrates Exhibit will have a special section on this species that exists no where else in the Universe but for a few creeks in the District of Columbia (and possibly Maryland)! But no. Lots of cool animals with no backbones: giant land crab, charismatic cuttlefish, ephemeral jellyfish, but no mention of DC's own very special and endangered crustacean. How could this be? Why isn't this little critter on the

|

| Not Hay's Spring Amphipod, but a close relative (Pizzini's Amphipod, Stygobromus pizzini). Photo by Brent Steury, National Park Service. |

Perhaps because it is a lowly, pale and blind amphipod that lives in mud and water? Thomas Roscoe Rede Stebbing may have said it best when he wrote in 1899 of the lowly amphipods:

No panegyrist of the Amphipoda has yet been able to evoke anything like popular enthusiasm in their favour. To the generality of observers they are only not repelled because the glance which falls upon them is unarrested, ignores them, is unconscious of their presence.And indeed, Hay's Spring Amphipod (Stygobromus hayi) spends its life in groundwater near natural springs, so it's not likely something we'd see during a walk in the park. It's also not furry or doe-eyed. In fact it's pale and blind, feeds on rotting organic matter and is less than an inch long. But with a little bit of marketing, perhaps we could make this the DC mascot! An underdog creature for an underdog

But more seriously, I think the little amphipod would be an excellent reminder of how we humans have endangered life of all kinds, great and small, and that endangered species are everywhere, not just in exotic far-off places, but sometimes in our own backyards.

|

| Some of my own ideas for the DC official crustacean mascot. |

Thursday, June 30, 2011

I am what I eat

|

| Me and some plantains, Portoviejo, Ecuador. |

|

| From the Hall of Human Origins, National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC. |

*Ecuador also produced me, a long time ago.

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

Gay pride, genes and brains

This post is part of the Diversity in Science Pride Blog Carnival: Pride Month 2011 edition.

Having grown up very early on as both an avid student of Darwin’s ideas and an earnest follower of the Roman Catholic faith, puberty posed for me a painfully confounding paradox: how could a nice church-going boy who read biology text books for fun find himself attracted to the same sex, an implausible urge that both my religion and science deemed abnormal and maladaptive? Hormones and peer-pressure can make life a bit problematic for many teenagers, but for a gay one who made sense of his world through the lens of biology and Catholicism, life suddenly became unfathomably perplexing, and quite depressing.

But it was biology that would help rescue me from the emotional tailspin. It was in the early 1990s that two highly publicized studies came out on biology and sexual orientation. These were Simon LeVay’s brain structure studies and Dean Hamer’s genetic linkage studies of gay men.

LeVay published results in 1991 that indicated differences in the structure of a small part of the brain when comparing the brains of homosexual to heterosexual men. The difference was reported to be in the third Intersitial Nucleus of the Anterior Hypothalamus (INAH3). This small bundle of neurons was more than twice as large in heterosexual men as it was in homosexual men. The reduced size of INAH3 was also observed in heterosexual women.

Figure of the INAH3 region of the hypothalamus courtesy of simonlevay.com.

In 1993, Hamer and colleagues published a study of a linkage analysis among gay men. The report indicated that among the gay male subjects, there was a higher frequency of gay male uncles and cousins on the mother’s side than on the father’s side of the family, suggesting there might be maternal inheritance of genetic determinants of homosexuality. The study went on to test for X chromosome linkage among the gay subject, and found a linkage between homosexuality and a stretch of the X chromosome called Xq28.

Figure of the X chromosome and the Xq28 region courtesy of NCBI.

Both these studies resulted in a frenzy of media coverage, with headlines about “the gay brain” and “the gay gene” splashed across magazine covers and newspaper front pages. For a young student of biology, it was always thrilling when science made its way to the top stories in the news. But this time it was personal. These studies told me that there might be a biological basis for the variation in sexual behavior among humans. And that if it was in the genes and in the brain circuitry, and thus not a choice as many proposed, why struggle and suffer needlessly to change it?

Of course, these studies had their critics. The LeVay brain data showed a correlation, but did not clarify if the brain structure variations were the cause or result of homosexual behavior. And the Hamer study never actually pinpointed to a specific gene allele that determined sexual orientation, but to a whole region of the X chromosome, and while some studies recapitulated the results, others did not, as is often the case in studies on the genetic underpinnings of such complex traits as human behavior. Still, the studies came out at the right time for me to come out. Not only did the findings appeal to my scientific way of thinking, but they also brought the talk of sexual orientation out into the open, on the news, on the covers of mainstream magazines, and into the lab and the world of biology.

Of course the coming out process did not magically become a piece of cake for me. But as a young scientist in the making, Dean Hamer and Simon LeVay were heroes to me, and their timely publication of their results made an unintended but hugely positive difference in my life.

Having grown up very early on as both an avid student of Darwin’s ideas and an earnest follower of the Roman Catholic faith, puberty posed for me a painfully confounding paradox: how could a nice church-going boy who read biology text books for fun find himself attracted to the same sex, an implausible urge that both my religion and science deemed abnormal and maladaptive? Hormones and peer-pressure can make life a bit problematic for many teenagers, but for a gay one who made sense of his world through the lens of biology and Catholicism, life suddenly became unfathomably perplexing, and quite depressing.

But it was biology that would help rescue me from the emotional tailspin. It was in the early 1990s that two highly publicized studies came out on biology and sexual orientation. These were Simon LeVay’s brain structure studies and Dean Hamer’s genetic linkage studies of gay men.

LeVay published results in 1991 that indicated differences in the structure of a small part of the brain when comparing the brains of homosexual to heterosexual men. The difference was reported to be in the third Intersitial Nucleus of the Anterior Hypothalamus (INAH3). This small bundle of neurons was more than twice as large in heterosexual men as it was in homosexual men. The reduced size of INAH3 was also observed in heterosexual women.

Figure of the INAH3 region of the hypothalamus courtesy of simonlevay.com.

In 1993, Hamer and colleagues published a study of a linkage analysis among gay men. The report indicated that among the gay male subjects, there was a higher frequency of gay male uncles and cousins on the mother’s side than on the father’s side of the family, suggesting there might be maternal inheritance of genetic determinants of homosexuality. The study went on to test for X chromosome linkage among the gay subject, and found a linkage between homosexuality and a stretch of the X chromosome called Xq28.

Figure of the X chromosome and the Xq28 region courtesy of NCBI.

Both these studies resulted in a frenzy of media coverage, with headlines about “the gay brain” and “the gay gene” splashed across magazine covers and newspaper front pages. For a young student of biology, it was always thrilling when science made its way to the top stories in the news. But this time it was personal. These studies told me that there might be a biological basis for the variation in sexual behavior among humans. And that if it was in the genes and in the brain circuitry, and thus not a choice as many proposed, why struggle and suffer needlessly to change it?

Of course, these studies had their critics. The LeVay brain data showed a correlation, but did not clarify if the brain structure variations were the cause or result of homosexual behavior. And the Hamer study never actually pinpointed to a specific gene allele that determined sexual orientation, but to a whole region of the X chromosome, and while some studies recapitulated the results, others did not, as is often the case in studies on the genetic underpinnings of such complex traits as human behavior. Still, the studies came out at the right time for me to come out. Not only did the findings appeal to my scientific way of thinking, but they also brought the talk of sexual orientation out into the open, on the news, on the covers of mainstream magazines, and into the lab and the world of biology.

Of course the coming out process did not magically become a piece of cake for me. But as a young scientist in the making, Dean Hamer and Simon LeVay were heroes to me, and their timely publication of their results made an unintended but hugely positive difference in my life.

A music video to launch SOSCIENCE

This is the first post in a blog devoted to science and society: SOSCIENCE!

Thomas Dolby - She blinded me with science

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)